A Framework for Competitive Advantage in Gaming

There are durable patterns for establishing competitive advantage in gaming. Investors and founders would do well to heed its history - venture exists to build great companies not products.

The pandemic was a great time for gaming. Stuck in lockdown, we gamed. Money was cheap as the Fed pumped liquidity into the economy. Unspecialized capital hurled itself at the gaming industry causing valuations to soar.

But the music has stopped. Money has a cost again, and gaming’s tremendous topline growth has hit a roadblock. Market conditions for almost all newcomers are unfavourable - founders need a clear strategy for establishing competitive advantage.

There are core characteristics that characterise remarkable startups in gaming, that separate a founder building a great product from one building a great company. The enduring pattern in gaming is the use of arbitrages (particularly in distribution) to generate enough momentum to build out platforms. Platforms, which combine services/tooling/products with an online community, are invaluable because they harness some combination of network effects, switching costs and scale economies.

Those patterns were ignored during the frothy years, but are more relevant than ever now.

- - -

Warren Buffet quipped that “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” The quip comes to mind when I recall the frenzied venture activity in gaming during the covid period.

2020-2 was a speculative bubble - buzzwords, FOMO and greed attracted unspecialized capital that, finding the rest of its portfolio on fire, sought to alleviate its woes by stripping naked and dive-bombing the alluring waters of gaming.

Growth at any cost became the mentality of the day, studios ran up burn rates of $3mn a month (Riot shipped on ~$20mn over years for perspective), aggressive user growth forecasts drove valuations sky-high with little consideration towards profitable growth and healthy balance sheets.

In the textbook speculative cycle, a disparity grows between the financial economy and the real economy its valuations are anchored to until catalytic developments force hard questions. Valuations cannot be justified, forecasts need to be revised; all of a sudden, efficiency, cost-tightening, lay-offs and a renewed focus on profitability become the new normal.

Those hard questions, which are brilliantly explored in Matthew Ball’s The Tremendous Yet Troubled State of Gaming and Gamecraft, have a silver-lining. During such periods there are exciting innovations in response to the crisis paired hand-in-hand with a return to remarkableness.

Indeed, there are durable patterns for the establishment of competitive advantage in gaming which involves transitional gear-changes. Like crushing the same RPG second-time round with a different build, new technologies allow creative re-explorations of those tried-and-tested patterns.

A Framework for Competitive Advantage in Gaming

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers is an excellent text on how founders, by leveraging certain powers, can create a great company with strong moats. Those 7 powers are:

Scale Economies: A business in which per unit cost declines as production volume increases.

Network Economies: The value of a service to each user increases as new users join the network.

Counter Positioning: A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

Switching Costs: The value loss expected by a customer that would be incurred from switching to an alternative supplier for additional purchases.

Branding: The durable attribution of higher value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historic info about the seller.

Concerned Resource: Preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value.

Process Power: Embedded company organisation and activity sets which enable lower costs and/or superior product.

It is necessary to prioritise and reorganise these powers in light of the unique challenges posed by the gaming industry. The fact that there have only been 15 IPOs in gaming (of which 7 were in the frothy covid years) is partially explained by liquidity dynamics, but it also speaks to the immense difficulty of constructing a great gaming company (and the identification of founders doing so).2

Given the two perennial critiques of gaming: it is hits-driven and has long time-to-product timelines, it is difficult for any founder to initially access process power, network economies or switching cost powers.

Veteran founder David Kaye makes this point about access to different competitive advantages at different stages in a recent blog post. He observes that it is necessary to break the powers up into different stages at which they can be accessed.3

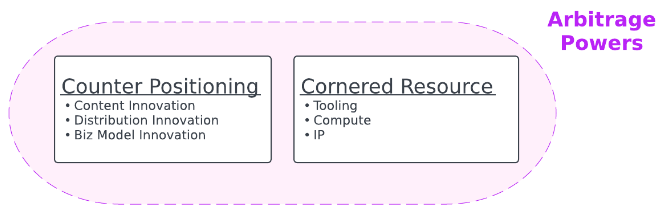

We can group Helmer’s powers into three distinct groupings that form a transitionary process:

‘Arbitrage’ Powers

With incumbents committed to existing product pipelines, distribution methods and business models, start-ups exploit market inefficiencies with arbitrages that build momentum in audience aggregation.

‘Platform’ Powers

The opportunities in these arbitrages are closed off as more participants explore them - great companies develop platform structures, leveraging their initial success in aggregating a dedicated audience. Platforms, benefitting from some combination of network effects, switching costs and scale economies, both snowball and entrench their audience.

‘Longevity’ Powers

Given the time to entrench themselves, expertise in the field creates development/R&D moats and the awesome value of brand-power in a hits-based industry.

‘Arbitrage’ Powers

David Kaye: “Startups have few advantages relative to much larger and better resourced competitors. The two origination powers turn these seeming disadvantages into strengths.”4

A quick word on definitions - I do not mean arbitrage in the technical trading sense of buying low and selling high. Rather, I mean it in the conceptual sense that: a) at any point in time, there exist economic inefficiencies that can be exploited and b) the widespread exploitation of these inefficiencies reduces their opportunity, and therefore, it is necessary to transition into leveraging ‘platform’ powers.

Counter positioning is by far the most common power deployed in content. Facing the innovator’s dilemma, incumbents are typically committed to existing models. This dilemma, alongside new technologies, create arbitrage opportunities for founders.

The historical lessons of this power were ignored in the recent speculative frenzy as $30bn of venture capital in 2020-2 hurled itself at the industry, and 2023 saw its consequences.

That 2023 was simultaneously one of the best years ever for game releases whilst mass lay-offs continued is not a contradiction, it is connected. Overfunding primarily chased content at the expense of innovation in a) distribution and b) business models.

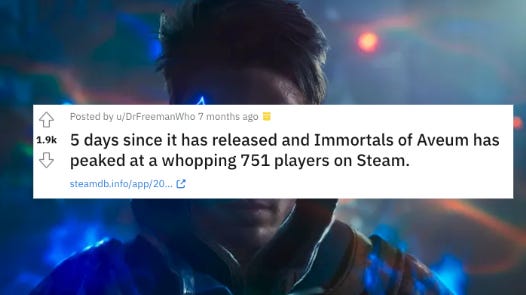

Take the flopped release of Immortals of Aveum. The commentary is revealing: “We absolutely got lost in the noise,” the dev team said. “Although the game was better, the timing was worse.”

There was, in the words of Mitch Lasky, “too much thinking on how to make a great game, and too little on how to deliver it.”5

Questions of USPs and distribution tactics fell by the wayside as venture funds stopped asking the most important question: is this a good company or just a good product?

I agree that content innovation is important. However, a sole preoccupation on it loses sight of one simple truth - that time and time again, distribution and business model innovation has proved the greatest arbitrage opportunity.

League of Legends is a great game, but the gameplay was not revolutionary (and I have played Gen 1 up until the present - waltzing around with Ashe’s lego-blocks shoes for years), its distribution strategy and business model was.

They had leveraged access to the audience of DOTA players. They invested in reaching those players on Reddit, hiring the modders from that community to join the dev team for good will, i.e. distribution innovations - a way of accessing an initial base of customers without having to pay hefty UA. Bringing the free-to-play model killing it in Asia back to the US was both a key business model innovation and a distribution game-changer.

This is not a one-off. Think back to many of the biggest titles. Sure, there was great content innovation, but the key arbitrage was usually distribution:

Fortnite did not invent Battle Royale, but they did pioneer cross-platform compatibility.

Apex Legends launched using streamers - a group which back in 2018 was relatively disorganised, so offered eyeballs on the cheap.

In the content space, I see this trend replaying itself in Look North World. One of the main challenges right now is the cost to develop. Halo Combat Evolved cost around $10-20mn, whilst Halo Infinity cost around $0.5bn - a 33x cost increase that has not been matched at the topline.6 That very visionary behind one of the greatest games of all time, Alex Seropian, is now using Unreal Engine for Fortnite to launch game modes with lower time-to-products and development costs.

But I believe this UGC developer model is a transitional strategy. Time and time again, the world’s biggest games have come from mods. I think the true long-term value is in: (1) aggregating an FPS audience into a Look North World ecosystem on Discord and (2) using Unreal Engine for Fortnite to sustainably iterate on game modes that appeal to that audience.

“Through experimentation, we will see what the players like and involve them in decisions… as we develop creative ideas, we will learn how these platforms engage, entertain and boost social interactions in order to iterate accordingly.” - Alex Seropian

In the future, that opens the door to launch a tried-and-tested product that is already popular with an audience aggregated from its Discord ecosystem. Reducing initial UA costs, and potentially, providing enough momentum to launch its own platform that is not hit by UGC/Platform-publishing fees (i.e. the Riot approach).

Cornered Resource is the other major arbitrage strategy. Gaming’s greatest impulse has always been its position at the frontier of Moore’s Law. New technological breakthroughs constantly create arbitrage opportunities.

Unity is a pertinent case study, here. When Apple launched its App Store in 2008, Unity had already spent the last 3 years pioneering its game engine and swiftly realised there was a major arbitrage opportunity at stake. Having already pioneered a networking layer in 2007 that allowed developers to create multiplayer games that offered state synchronisation, remote procedure calls and network address translation, its priority was to add support to the iPhone and, within years, around 50% of mobile games were made with the Unity engine.

Note that Unity recognised this was an arbitrage and they needed to transition - leveraging their aggregated audience from their game engine to build an advertising platform for mobile developers that could leverage network effects and a scale economy. The real cash cow for Unity is the various services, analytics, advertising and cloud hosting solutions that help developers monetize and scale their creation (Unity Create [engine business] reaped $189mn vs Unity Grow’s $355mn in Q3 23).

This failure to transition into more durable competitive advantages is, arguably, the core mistake that made much of the mobile gaming industry so vulnerable to Apple’s deprecation of IDFA. Much has been written on this subject, highlighting how the reduced ability of mobile ad networks to deliver personalised advertising to users has diminished ad revenue and efficacy.

But I would add that it was also a failure of competitive strategy. “The ability to buy users more cheaply than competitors is not a long-term sustainable advantage. It is simply an arbitrage that will be closed” (Mitch Lasky). 7 An excessive reliance on an arb of monetising whales with marketing spend at ~90% of net revenue came at the expense of transitioning into more enduring moats.

The desire and ability to transition from arbitrage powers into platform powers is what separates great companies from great products.

‘Platform’ Powers

Henri Holm, ex-Rovio Senior Vice President: “Market conditions for almost all newcomers are not favourable or feasible unless you have strategies in place that allow a strong network effect.”

The late ‘00s into the ‘10s saw the rise of the platform based publisher - a new idea for how to structure games for the internet age. It combined two ideas. 1, the idea of platform: software that creates low friction links between gamers and developers and 2, publishing goods and services at scale.

Valve wrote the textbook here, leveraging the success of Half Life and CSGO to kick off Steam’s distribution revolution (digital shipping offered developers zero additional marginal cost for shipping beyond the initial fixed cost of uploading the first copy) and exponential network power kicked in once 100mn+ credit cards were registered to the platform.

The last five or so years have seen the rise of software driven game-enabling platforms. By bringing together core services, tooling or content with online communities, these platforms leverage some combination of scale economies, network effects and switching costs. Platforms like Epic, AppLovin, Roblox and Discord have created considerable enterprise value that has allowed them to trade at a premium to their peers, Roblox’s EV hovers around 11x annual revenue versus the video game average of 4-7x.

Epic is a great example of a company repeatedly iterating to carve out a successful platform. Leveraging the popularity of Fortnite, it launched the Epic platform hoping to knock Steam off its perch with a 12% take rate (Steam’s is 30%).

Its failure thus far to do so is testament to the immense value of network effects. That +18% is not sufficient because Steam more than earns that premium by offering the best place to attract a pre-qualified user, who in turn, is likely to bring in their friend network (let’s recall that there is always the option to distribute a game from your own platform with no take rate, and yet few pursue this avenue).

So Epic pivoted to the UGC platform-approach. They made their most popular product, Fortnite, a platform. The decision to share 40% of net revenue from Fortnite with developers to create new experiences is extremely bold. They have cut their margins on the game overnight, but the potential gains of establishing a platform make this worthwhile.

Look at Roblox: large audiences pull in developers. New games from said developers pull in and retain that audience. Over time, the revenue becomes increasingly captive. Net, it is estimated that only 29% of revenue goes to game creators after the various taxes to Robux and Robux-to-USD are applied.

Turning to mobile, AppLovin was an arbitrage that transitioned into a highly lucrative platform. In 2011, the founders realised there were apps that had lots of users but were struggling to monetise, e.g. Fart. The easiest way for them to monetise was through ads - so they started by connecting them with developers looking for users.

This allowed the transition into a two-way network. On one side of their platform, there are the apps that want to find new users that form the basis for ad spend. They can pick ad campaign parameters and goals (e.g. ROAS). Those ads are matched using a recommendation engine, then bid against each other in milliseconds to be served to the other side of the network - app developers seeking monetisation.

The true genius of AppLovin, though, was their realisation of the value of training data. Given recent generative AI developments, it seems almost prophetic. They produce over 200+ games, but notably, they treat their game arsenal as the cost necessary to gain access to a more lucrative commodity - first-party user data. Their ML engine, the AXON recommendation system, is trained on said first-party data to find and recommend users most likely to engage with the app. They are far more immune from the IDFA’s deprecation because they are sitting behind a walled garden of first-party data.

They recognised very early on that one of the most valuable assets a scaled platform possesses is data. That is prescient - with researchers estimating that by 2026 we will have exhausted high quality training data, those with access to proprietary user data will become acquisition and licensing targets.

We are already seeing this trend of data scarcity driving up its value. The gaming platform’s ability to both build richly detailed user accounts (emails, names, age, gender, address) and host online discussions will prove increasingly lucrative.

To sum, platforms are invaluable because they harness some combination of network effects, switching costs and scale economies, but they are not easily accessible. Therefore, the enduring pattern in gaming is the use of arbs to create initial audience momentum to build out platforms.

Investors and founders alike would do well to heed this history - the role of venture funding is to build companies not products.

Another benefit of entrenching a competitive advantage this way are the increased odds of surviving long enough to access the powers of branding and process power (3, longevity powers).

Merely surviving long enough with enough users at scale is invaluable, because it provides the revenue to further entrench developer/R&D moats.

This is the catch-22 that has hindered web3. The most feasible way to bring in new players is to make NFTs and coins free. Release them to the initial player-base to attract new users, and hopefully, they increase in value to create a third-party market (that developers might take a cut of). So far no developer has been really able to pull this off to accrue enough revenue to support the live-dev game. Various ‘AAA’ web3 releases in the pipeline, e.g. Metalcore, appear reliant on standard web2 monetisation schemes to compensate for this.

Final Thoughts

I am cautiously optimistic about the gaming industry. It is going to be a choppy few years which will require a stricter focus on remarkableness. A focus on great companies over great products. A focus on how new technologies can be used to re-explore those durable patterns for the establishment of competitive advantage through transitional powers.

Avatar Aang (humble-brag I hit 100% completion in my first year of uni playing the 2014 Legend of Korra game) remarks that “when we hit our lowest point, we are open to the greatest change.” The gaming industry is at a low point, but that is also a source for excitement.

The future and its new technologies are there to be grasped, provided that an understanding of the past is also present.

***

Thank you for reading! Please do reach out to me at RonanColPatrick@gmail.com, on LinkedIn or on Discord (Skrufy#3945) if you found this piece interesting.

“The Tremendous Yet Troubled State of Gaming in 2024”, Matthew Ball

“The 7 Paths to Power”, David Kaye

Ibid

“The Tremendous Yet Troubled State of Gaming in 2024”, Matthew Ball

CB Insights - Generative AI Predictions 2024